FFNs

Materials:

Date: Saturday, 07-Sep-2024, 1.30pm, IST.

Pre-work:

- Refresh ML foundations.

- Read “The 100 page ML book” by Andiry Burkov. Chapters accessible here

In-Class

- History of Deep Learning

- Lecture-1 pdf, Interactive slides [R01]

- Lecture-1 pdf [R02]

- Visualizations

- Interactive Figures to visualize NNs [R05]

- Representational Power of NNs from [R06]

- Neural Networks Motivation

- McCulloch-Pitts Neuron, Perceptron Lecture-2:pdf [R01]

- Digital Logic Modeling by Perceptron Neural Networks:pdf [R03]

- FFNs

Lab

- FFN for Classification on Iris data

- FFN for Regression on Friedman2 data

Post-class:

- Lecture-3:pdf Sigmoid Neuron, Error Surfaces, Representation Power of FFNs [R02]

- Gradient Descent, Word Vectors [R03]

- Lecture-4:pdf FFNs and Backprop [R02]

- Computational Graphs, Backprop:pdf [R03]

- Lecture - Expressivity and UAT

- Neural Networks Review from R07

- Neural Networks: A Review part-1: youtube, part-2: youtube

- FFNs and Backpopr part-1: youtube, part-2: youtube

Papers

- Universal Approximation Theorem original paper by Cybenko pdf

- Multilayer FFNs are universal approximators Hornik, Stinchcombe, and White

- Representation Benefits of Deep FFNs Telagarsky

Notes

Linear Model

Consider the following regression problem \[y^{[i]} \equiv f(x^{[i]}) + e^{[i]} \equiv \phi(x^{[i]}) + e^{[i]}, i \in \left\{1,\dots,N\right\}\] with \(D = \{x^{[i]}, y^{[i]}\}_{i=1}^{N}\) representing all the data available to fit (train) the model \(f(x)\). Suppose that \(x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_{n_0}\) are the \({n_0}\) features available to fit the model. If we choose \(f(.)\) to be a linear combination of the features, it leads us to the familiar Linear Model (or Linear Regression). In matrix notation, the regression problem is: \[ \begin{array}{left} {\bf y} = {\bf X}{\bf \beta} + {\bf \epsilon} \end{array} \] where \[ \begin{array}{left} {\bf X}_{N \times {({n_0}+1)}} &=& \begin{pmatrix} 1 & x_1^{[1]} & \dots & x_{n_0}^{[1]} \\ 1 & x_1^{[2]} & \dots & x_{n_0}^{[2]} \\ \vdots & & & \vdots \\ 1 & x_1^{[N]} & \dots & x_{n_0}^{[N]} \end{pmatrix} \\ {\bf \beta}_{{({n_0}+1)} \times 1} &=& [\beta_1, \beta_2, \dots, \beta_{({n_0}+1)} ]^T \\ {\bf y}_{N \times 1} &=& [y^{[1]}, y^{[2]}, \dots, y^{[N]} ]^T \\ \end{array} \] This is the classic Linear Regression setup. To recast this in a familiar Deep Learning notation, we rewrite the above as: \[ \begin{array}{left} {\bf y} = {\bf X}{\bf w} + {\bf b} + {\bf \epsilon} \end{array} \] where \({\bf b}\) represents the \({n_0} \times 1\) bias (or intercept) term, \({\bf w}\) is the weight matrix (regression coefficients) and \({\bf X}\) is the set of all \(N \times (n_0+1)\) features excluding the column of ones (which was included to model the intercept/ bias term).

The prediction \({\bf \hat{y}}\) is typically the conditional expectation \({\bf \hat{y}| {\bf X} } = {\bf X}{\bf w} + {\bf b}\) under the zero-mean error model for \({\bf \epsilon}\), obtained by minimizing the MSE between the observed and the predicted. This is essentially a Perceptron with linear activation function, which is typically used to solve regression problems. What about binary classification (or more generally, categorical responses)?

Generalized Linear Model

Binary Classification

Suppose \(y \in \{ 0,1\}\) is a binary response, and consider the following (generative) model:

\[ \begin{array}{left} y^{[i]} = I(h^{[i]} \ge 0) \\ h^{[i]} \equiv f(x^{[i]}) + e^{[i]} \end{array} \]

Notice that the output is a thresholded version (via the Indicator function) of the linear model response \(h^{[i]}\). If \(e^{[i]} \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\), then,

\[ \begin{array}{left} P(y^{[i]} = 1) \equiv \pi^{[i]}= \sigma \left( f(x^{[i]}) \right) \equiv \frac{ \exp(f(x^{[i]})}{1+ \exp(f(x^{[i]}))} \end{array} \]

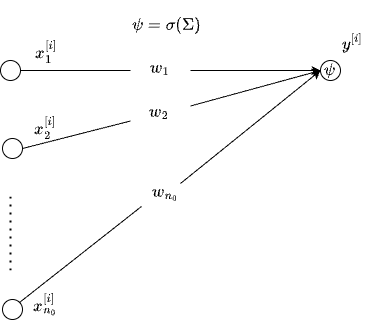

If we choose \(f(x^{[i]}) \equiv {\bf x}{\bf w} + {\bf b}\), where \({\bf x}\) is \(1 \times {n_0}\) vector of inputs, we recover the Perceptron with sigmoid activation, which is exactly the Logistic regression model, belonging to the much larger class of Generalized Linear Models (GLMs). In the place of \(\sigma\), one can choose any CDF. In particular, if we choose the CDF of the standard Normal distribution, we recover the Probit model. This Perceptron (Logistic regression) is the most recognizable building block of MLP, a schematic of which is shown below.

Multiclass Classification

The extension of the logistic regression to multiclass is straightforward but we need a different way of writing the models. The Binary Classification problem can written in the following equivalent fashion: \[ \begin{array}{left} y^{[i]} \sim Bin(\pi^{[i]}, 1)\\ \pi^{[i]} = \sigma \left( f(x^{[i]}) \right) \equiv \frac{ \exp(f(x^{[i]})} {1+ \exp(f(x^{[i]}) } \end{array} \] In the GLM nomenclature, it is customary to link \(\pi^{[i]}\) with \(f(x^{[i]})\) as follows: \[\log\left(\frac{\pi^{[i]}}{1-\pi^{[i]}}\right) = f(x^{[i]})\] It is like \(f(x^{[i]})\) is now modeling the difference in the class-specific responses. To make this explicit, suppose, \(f_k(x^{[i]})\) is the class-specific latent response (whose thresholded version yields the binary response as noted before). Then, by specification, \(f(x^{[i]}) = f_1(x^{[i]}) - f_0(x^{[i]})\). It follows then that, \[ \begin{array}{left} \pi^{[i]} &=& \frac{ \exp(f(x^{[i]})} {1+ \exp(f(x^{[i]}) } \\ &=& \frac{ \exp(f_1(x^{[i]}) - f_0(x^{[i]})) } {1+ \exp(f_1(x^{[i]}) - f_0(x^{[i]})) } \\ &=& \frac{ \exp(f_1(x^{[i]})} {\exp(f_1(x^{[i]}) + f_0(x^{[i]})) } \\ &\equiv& \text{softmax}(f_1(x^{[i]})) \end{array} \]

Vector Generalized Linear Model

Now we are in a position to extend the Binary Classification problem to the Multiclass setting, where the scales are nominal (i.e., the class labels have no ordering, and labels could have been shuffled with no consequence).

Suppose we have \({n_L}\)-classes with \(\pi_k^{[i]}\) representing the i-th example being drawn from the class \(k\) with \(\sum_{k=1}^{{n_L}} \pi_k^{[i]} = 1\). The following generative model is a plausible model: \[ \begin{array}{left} y^{[i]} &\sim& \text{Multinomial}(\pi_k^{[i]}, 1)\\ \pi_k^{[i]} &=& \frac{\exp(f_k(x^{[i]})}{ \sum_k \exp(f_k(x^{[i]})} &\equiv& \text{softmax}(f_k(x^{[i]})) \end{array} \]

Notice that, we have one hidden/ latent functional for each class \(f_k(x^{[i]})\) - the normalized version of which models the class probabilities in the Multinomial distribution. In general, in the above model, all \(f_k(.)\) are not identifiable. In fact, under the simplex constraint (i.e., class probabilities must add up to to one), \(\sum_k f_k(.) =0\), which essentially is saying that, to model \(n_L\) responses, we can not have \(n_L\) independent (unconstrained) latent responses but only \(n_L-1\) are identifiable.

As a check, if we place this simplex constraint on the logits for the Binary Classification, we can recover standard logistic regression model, as shown below: \[ \begin{array}{left} \pi^{[i]} &=& \frac{ \exp(f_1(x^{[i]})} {\exp(f_1(x^{[i]}) + f_0(x^{[i]})) } \\ &=& \frac{\exp(2 f_1(x^{[i]})-1)} {1+ \exp(2f_1(x^{[i]}-1))} \because f_1(x^{[i]}) + f_0(x^{[i]}) =0 \\ &=& \frac{\exp(f(x^{[i]})} {1+ \exp(f(x^{[i]}))} \text{ with } f(x^{[i]}) = 2f_1(x^{[i]})-1 \\ &\equiv& \sigma (f(x^{[i]})) \end{array} \]

Digression: In the Deep Learning context, such explicit constraints are ignored. When training the models with SGD, different tricks which are empirically proven such as Layer Normalization, Batch Normalization etc are used. Their effect is to enforce identifiability constraints via what look like hacks but in reality, they are fixes for the structural issues in the models themselves.

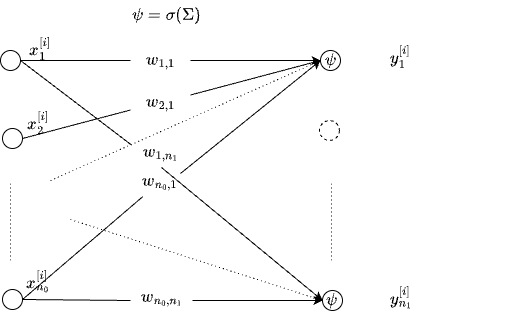

When the constrains are removed, and \(f_k(x)= {\bf x}{\bf w_k} + {\bf b_k}\) is a linear model, we get a Vector Generalized Linear Model (VGLM). VGLAM is shown as a (shallow) network below.

Specifically, ignoring the bias terms for simplicity, \[ \begin{array}{left} y_k^{[i]} \equiv \psi(x^{[i]}) = \sigma \left( \sum_{j=1}^{n_0} w_{j,k} x_j^{[i]} \right) \forall k=1,2,\dots n_L\\ \end{array} \] Here \(\sigma(.)\) is element-wise operation. So far we discussed the shallow Perceptron for regression, and classification. It is often helpful to write the expression in matrix notation as follows: \[ \begin{array}{left} \bf{y} = \sigma \left( xW+b \right) \end{array} \] where we have added the bias term \(b\), a \(n_L\times 1\) vector, \(x\) is \(1 \times n_0\) input vector, \(W\) is a \(n_0 \times n_L\) weight matrix. How can we add depth?

Deep Vector Generalized Linear Model

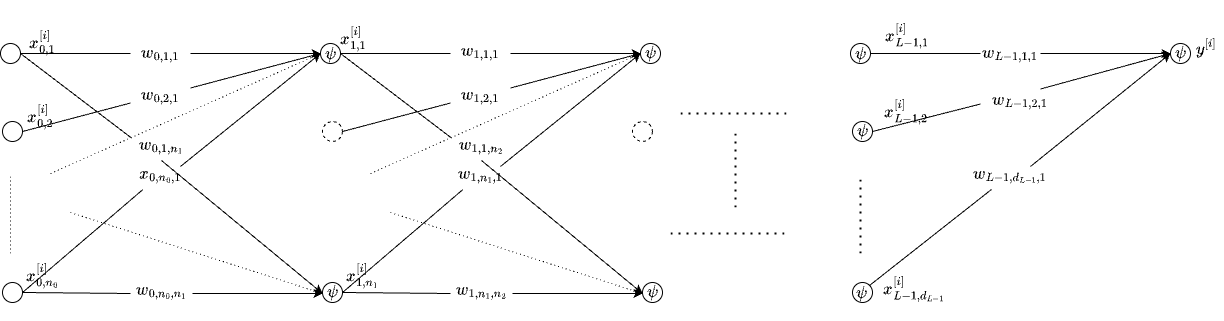

At the heart of the GLM for Multiclass, we have \(f_k\) which is a map from \({n_0}\)-dimensional input to \(R\), i.e., \(f_k(): R^{n_0} \rightarrow R\). If we have \({n_L}\) such functions, we effectively have \(f: R^{n_0} \rightarrow R^{n_L}\). We can stack such blocks to get a composition as follows:

\[ f(\bf{x})= \sigma\left( \dots \left( \sigma\left(x W_0 + b_0\right)W_1 + b_1 \right) \dots \right) W_{n_{L-1}} + b_{n_{L-1}} \]

The above is the popular Multilayer Perceptron or MLP as it is known. Shown below is the network without the bias terms.

Universal Approximation

2-Ary Boolean Circuits

Let us consider boolean variables and just two inputs \(x_1, x_2 \in \{0,1\}\). We will model the popular logic gates using a simple Neuron: \(y = H\left(x_1 w_1 + x_2 w_2 + b\right)\), where the Heavyside step function \(H(x) = 1 \text{ if } x\ge 0, 0. \text{ o.w}\)

| gate | \(w_1\) | \(w_2\) | b |

|---|---|---|---|

| AND | 1 | 1 | -1.5 |

| OR | 1 | 1 | -0.5 |

| NAND | -1 | -1 | 1.5 |

| NOR | -1 | -1 | 0.5 |

For example, the Truth Table for AND, and the corresponding output realized by the Neuron is given below:

| \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | \(y_{AND}\) | \(\hat{y}_{AND}\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | \(H(-1.5)=0\) |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | \(H(-0.5)=0\) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | \(H(-0.5)=0\) |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | \(H(+0.5)=1\) |

Other gates like NAND, NOR and OR can also be realized by a Neuron of the form shown above. The NAND gate is called a universal gate (so does NOR) because, given enough number of NAND gates, any Truth Table can be realized consisting of only NAND gates. For example, NOT gate can be realized by setting one of the inputs to logic 1 to get the complement of the other input. Note that XOR can not be modeled by a Perceptron. Can you guess why?

M-Ary Boolean Circuits

Now we will generalize the above for M-ary AND, NAND, OR and NOR gates as follows. \[ \begin{array}{left} \hat{y}_{AND} = \text{H}(\sum (x_i-1) \,+ 0.5)\\ \hat{y}_{NAND} = \text{H}(\sum(1-x_i) \,- 0.5) \\ \hat{y}_{OR} = \text{H}(\sum x_i \,- 0.5) \\ \hat{y}_{NOR} = \text{H}(\sum -x_i \,+ 0.5) \\ \end{array} \] Verify the results yourself.

M-Ary Universal Boolean Circuits

Now consider M-ary inputs and our goal is to build a boolean circuit which can realize any Truth Table. The Truth Table consists of \(2^M\) rows, each row corresponding to one specific state of the inputs, and contains \(M+1\) columns - one column for each of the \(M\) inputs and one column for the output \(y\). Truth Table can be realized in the form of a Sum-of-Products (SoP) form, a special form of Disjunctive Normal Form (see Canonical Forms to represent Truth Tables in Boolean Algebra). Let us look at an example below with two inputs, modeling XOR gate:

| \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | \(y_{XOR}\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

For each row, whose Truth value is 1, we consider the product of inputs. We take the complement of the input when it is zero. For the XOR gate, we add the 2nd row product \(\bar{x_1}x_2\) to the third row term \(x_1 \bar{x_2}\) to get final SoP as follows: \[ y = \bar{x_1}x_2 + x_1 \bar{x_2} \] where \(\bar{x}\) represents the logical complement of \(x\). Notice that each product term consists of two sub products - one that is a product of all inputs where inputs are 1s, and product of their complements where the inputs are 0. Therefore, each product in the SoP can be represented as \(AND(AND(.), NOR(.))\) and refer to this as \(AANOR\) as contraction. For example, the first term in the SoP for XOR is \(AND(AND(x_1), NOR(x_2)) \equiv \bar{x_1}x_2\). We will exploit this to succinctly represent the SoP: \[ \begin{array}{left} y &=& \sum_{i \in \{ i' \text{ s. t } y^[i']=1\} } AND( AND( x^{i}_{p \in A}), NOR(x^{i}_{q \in \bar{A}})) \\ A^{[i]} &=& \{ p \text{ s.t } x_p^{[i]} = 1 \} \\ \bar{A}^{[i]} &=& \{ p \text{ s.t } x_p^{[i]} = 0\} \end{array} \] The outer sum in the SoP is nothing but an OR gate operating on the innards. Therefore, to realize an SoP boolean network, we need an N-ary OR gate (where N can be at most \(2^M\) where M is the number of inputs or input dimension). Then the inner gate is \(AANOR \equiv AND(AND(.), NOR(.))\). Can we realize such as a gate with a Neuron?

Boolean MLP

Observe that the AANOR gate is hot only when all \(x \in A\) are 1s and \(x \in \bar{A}\) are 0s. To clarify, the AANOR gate is hot for exactly one of the rows of the \(2^M\) rows. Exploiting this fact, we can simplify the Truth Table as follows:

| Case | \(x \in A\) | \(x \in \bar{A}\) | \(y_{AANOR}\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-1 | All 1s | All 0s | 1 | |

| Case-2 | All 1s | At least one 1 | 0 | |

| Case-3 | At least one 0 | Any | 0 |

Verify that cases are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Based on our idea about AND and NOR gates designed earlier, let us hypothesize the following Neuron for the AANOR gate as follows: \[ \begin{array}{left} y &=& H( \sum_{i \in A} (x_i-1) -0.5 + \sum_{i \in \bar{A}} -x_i + 0.5 + b) \\ &=& H( \sum_{i \in A} (x_i-1) + \sum_{i \in \bar{A}} -x_i + b) \end{array} \] where \(b\) is to be found out, which we do next.

Case-1: In this case, substituting the specific x’s, we get the inequality \(b > 0\), which ensures that \(H(.)=1\) in this case.

Case-2: All x’s in A are 1s and at least one x in \(\bar{A}\) is 1, implying, we want, \(\max \left( \sum_{i \in \bar{A}} -x_i + b \right) < 0\). It is \(-1+b\) and is achieved when exactly all but one x’s in \(\bar{A}\) are zero. Therefore, we get, \(1-b< 0\)

Case-3: At least one x in A is 0, which means, we need \(\max \left( \sum_{i \in A} (x_i-1) + \sum_{i \in \bar{A}} -x_i + b \right) < 0\). It is \(-1+b\) and is achieved when exactly one x in A is zero, and all x’s in \(\bar{A}\) are zero. Therefore, we get, \(b-1 < 0\) as in Case-2. We can choose \(b=0.5\) which satisfies both the inequalities \(0 < b < 1\). The AANOR gate can now be realized as:

\[ \begin{array}{left} y &=& H( \sum_{i \in A} (x_i-1) + \sum_{i \in \bar{A}} -x_i + 0.5) \end{array} \]

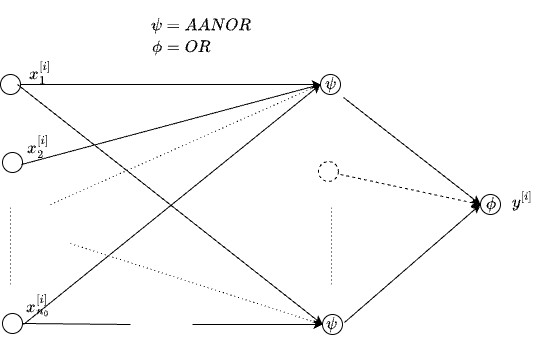

Now that we can realize any AANOR gate, and OR gate is something we have already seen, any M-ary Boolean Truth Table can be realized as \[ \begin{array}{left} y &=& OR(\{ AANOR(x^{[i]} \}), i \in \{ i' \text{ s. t } y^[i']=1\} \end{array} \]

Above can be seen a composition of Boolean gates which we can call as Boolean MLP (BMLP): \[

\text{ inputs > hidden (AANOR) > output (OR) }

\] which is indeed an MLP with 1-hidden layer in hindsight, as illustrated in the figure below.

Effectively, we exploited the fact that any M-ary Truth Table can be expressed in SOP form, and we have constructed a 1-hidden layer MLP which can exactly model the SoP.

Let us verify this circuit for XOR gate which we know can not be modeled by single Neuron but can be modeled by a 1-hidden layer MLP.

\[ \begin{array}{left} h_1 &=& H\left( (x_1-1) - x_2 + 0.5 \right) \\ h_2 &=& H\left( -x_1 + (x_2-1) + 0.5 \right) \\ y &=& h_1 + h_2 - 0.5\\ \end{array} \]

| \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | \(y_{XOR}\) | \(h_1\) | \(h_2\) | \(y=OR(h_1, h_2)\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Indeed, we recovered the XOR gate. Of course, we are operating on Boolean inputs. The continuous analogue of what we derived for MLPs with 1-hidden layer are due to the early works of Cybenko’s Universal Approximation Theorem pdf. A nice illustration of the Universal Approximation abilities of MLPs can be found here - Representational Power of NNs

M-ary SOP Implications

UAT from the lense of Boolean circuits opens up many interesting questions and potential answers to some of them. The critical observation is, in the discrete case, we see that the AANOR and OR gates consist of +/-1 as the weights and +/-0.5 as the bias terms. This can have many implications.

- Initialization:

- Draw the weights from \(w \sim N(\alpha(2h-1), \sigma_w^2), h \sim \text{Bernoulli}(0.5)\)

- Draw the bias terms from \(b \sim N(\alpha(h-0.5), \sigma_b^2), h \sim \text{Bernoulli}(0.5)\)

- Note that we have used \(\alpha=1\) in deriving a 1-hidden layer Boolean MLP. But different \(\alpha\) can be chosen. For example, with \(\alpha=20\), Sigmoid activation approximates the Heavyside step function well. For training MLP, w.l.o.g, one can choose \(\alpha=0.5\) to make the gradients well behaving.

- Lottery Ticket Hypothesis:

- The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis conjectured that, when networks are densely and randomly intialized, some sub-networks would reach test accuracy comparable to original network. In the discrete case, it would mean that some inputs are exactly mapped to the output (essentially a look up table). And a dense MLP would have implemented a soft version of the look-up table (this essentially shows again that all models are K-Nearest neighbors). The Boolean MLP might be an interesting model to probe the Lottery Ticket Hypothesis further.

- Pruning and 1-bit LLMs

- In the context Large Language Models (LLMs), we see large models with parameters in the order of billions are successfully getting compressed/quantized without much degradation in the performance. See for example, The Era of 1-bit LLMs. All LLMs are 1.58 bits. If all the weights are sampled from {-1,0,+1} they require \(\log_2(3)=1.58\) bits.

- The optimal Boolean MLPs are precisely 1 bit networks, but it is easy see that, the fully specified and overparametrized Boolean MLPs are 1.58 bits, where 0 weight models skip connections.

- Hardware Accelerators

- We are seeing a surge in hardware accelerators (and downstream toolchains including compilers, and hardware-software co-design) to make both training and inference faster.

- GPUs are the backbone of compute infra to train Deep Neural Nets. At the heart of it, it is the matrix multiplication that needs to be done efficiently. What if networks have no explicit MatMul operations - see Scalable MatMul-free Language Modeling for an approach or the more recent BOLD: Boolean Logic Deep Learning where networks are trained based on a new mathematical principle of Boolean Variation with considerations for chip architecture, memory hierarchy, dataflow and arithmetic precision.

- Can we directly burn the model onto silicon? That is, can we take a Boolean MLP specified in PyTorch and create HDL files using the latest and greatest in VLSI technology? See hls4ml project.

Summary

- Logistic regression is a member of Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

- GLMs are a member of Vector Generalized Linear Models (VGLMs)

- Logistic regression = Perceptron with sigmoid activation

- MLP with an input and output layer (with multiple outputs) = VGLM

- MLPs are Deep VGLMS

- Universal Approximation Ability of MLPs

- Any M-ary Boolean circuit can be represented in Sum-of-Products form

- AND, OR, NAND, NOR gates can be realized by Perceptrons.

- Sum-of-Products can be realized by an MLP with 1-hidden layer.

- (Therefore) MLP with 1-hidden layer is a Universal Approximator of (any) M-Boolean circuit

- Boolean MLPs open up interesting avenues to explore Weight Initialization strategies, Pruning, Hardware Accelerators, and studying loss surfaces.

Additional References

- Generalized Linear Models, a classic, by McCullagh and Nelder.

- Categorical Data Analysis, a classic, by Alen Agresti. His others books are nice too.

- Vector Generalized Linear and Additive Moldes T. W. Yee

Exercises

- Verify/Prove that M-ary AND, OR, NAND, and NOR logic gates in the notes are correct.

- Show that XOR can not be realized by a Perceptron

- Prove (by any other method) that AANOR gate is correct.

- In the notes we have used SoP form. But one can also realize Boolean circuits via Product-of-Sums (PoS). Design a 1-hidden layer Boolean network and show that it is also another Universal Approximator of an M-Ary Truth Table.

Mini Project

- Take a tabular data (Eg. Iris data but only consider two features) with numerical features, and Binary Class.

- Quantile Bin the features. Effectively, one hot code each feature where the bins represents the quantiles the sample belongs to.

- By now, we have turned the inputs to Boolean inputs. Output is already Boolean.

- Build a 1-hidden layer Boolean MLP

- Synthesize the circuit using hls4ml